High nitrogen feedstocks include biosolids, digestate, and some food waste. These feedstocks are often in abundant supply but are challenging to process with rudimentary processes like static piles or windrows due to their tendency to off-gas ammonia or remain in their anoxic state dominated by odorous anaerobic microbiology. This whitepaper outlines the steps necessary to get these challenging feedstocks into a BMP mix that can be maintained in aerobic conditions to minimize odor generation and maximize rates of compost stabilization.

There are a few simple Best Management Practices (BMPs) that can be regularly performed onsite at any composting facility and used to define Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). With regular data collection and an understanding of the BMP target range for each KPI, site operators can use this information to tune their process in order to minimize the generation of odors and VOC’s and better control the quality of their end product. The most critical points in the process to measure KPI’s and make adjustments are during the creation of the initial mix going into primary composting and then during the first few weeks of the active composting process. This short paper provides our recommendations for data collection at these two stages and a short explanation of why these parameters are critical.

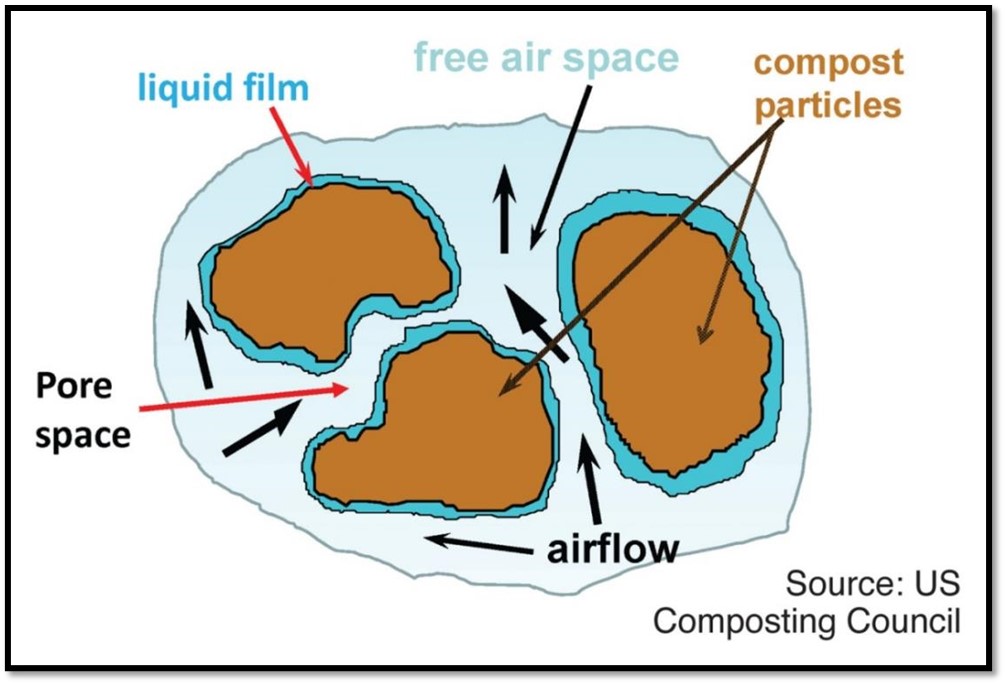

Starting with a BMP mix is critical to the entire compost process. There are three key KPI’s that should be measured and tracked: moisture, density, and C/N ratio. Since high nitrogen residual feedstocks (such as biosolids, manures, and digestate) are generally wet, dense, and high in nitrogen, they must be mixed with an amendment that is dryer, provides porosity, and contributes significant amounts of carbon. Proper mixing of these disparate feedstocks requires a device that effectively stirs and folds them (such as a batch mixer or a windrow turner). This gives rise a fourth qualitative KPI: “mix uniformity.” The three key KPI’s above are only significant if the mix is relatively uniform. These four parameters set the stage for conditions on the liquid film that surrounds the compost particles where the decomposition takes place.

When the mix KPI’s are all within BMP ranges, the subsequent composting process will have a chance of proceeding under optimal process conditions. If one or more parameters falls outside the BMP range, the process will become inhibited due to anoxic/anaerobic conditions (poor gas exchange) or high ammonia concentrations (due to low C/N) in the free air space resulting in dramatically slower stabilization and the generation of stronger odors

The table below outlines the three initial mix KPI’s we think should be measured and logged regularly to provide assurance that a BMP mix is being made each and every batch of compost.

| Key Process Variable | BMP Target | Method | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Density | 800-925 lb/cy | Bucket and scale | Composite sample each batch |

| Moisture Content | Moist not drippy | Squeeze test | 3-4 grab samples each batch |

| Moisture Content | 55-63% | Lab test to verify squeeze test | Quarterly |

| C/N Ratio | >25 | Lab test | Quarterly |

While the production of a BMP compliant mix requires the operator’s attention, sustaining BMP oxygen and temperature levels during active composting is largely dependent on the design of the aeration and control system. Consistently maintaining BMP conditions requires feedback-controlled aeration that automatically adjusts to meet the highly variable cooling demands of the biological process and achieve user defined process goals (such as PFRP). Further, the mechanical design of the aeration system must provide adequate peak flow rates (for cooling) and flow uniformly to keep the majority of composting volume within the BMP temperature and oxygen ranges. The peak design flow should be matched to the degradability of the feedstock mix; airflow rates between 5 – 10 cfm/cy of mix can be periodically required early in the composting cycle. Windrow composting airflow rates are generally less than 0.1 cfm/cy. Fabric covered systems usually restrict airflow rates to less than 1 cfm/cy.

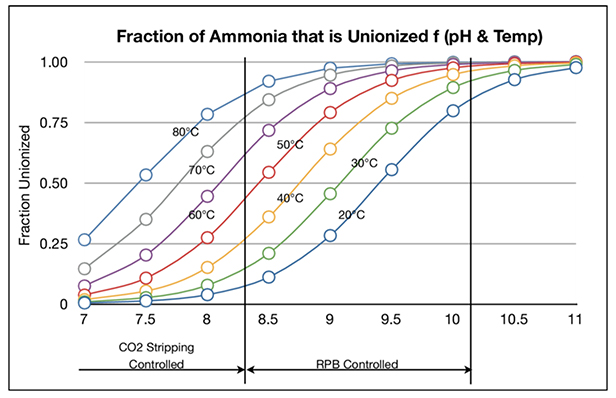

Ammonia commonly forms in biosolids composting and can inhibit both the process and biofilter effectiveness. While ammonia tends to dissipate quickly due to high vapor pressure (low boiling point), its’ presence can lead to formation of highly odorous compounds (like reduce sulfurs). Both pH and temperature determine the concentration of ammonium (NH4+) into free ammonia gas (NH3). By controlling temperature and monitoring the mix pH, the operator can manage ammonia formation.

Uncontrolled, the process can be severely impacted by free ammonia gas, dissolved into the liquid of the biofilm of each compost particle, and the process can be inhibited by its own toxicity (ammonia gas is toxic). However, with good temperature control, high air-change rates in the pore space, and a woody bulking agent to offset the alkaline pH of biosolids, the majority of the ammonium can be kept in ionized form (NH4+) where it is available to bacteria for cellular growth and oxidation of carbon compounds.

The figure below displays the relationships between ammonium and ammonia as affected by pH and temperature. As temperature increases, the fraction of unionized ammonia gas (NH3) increases and negatively impacts the composting process. A process at 50°C and pH 8.3 can have <50% of its nitrogen in ammonia gas phase, whereas that same process at 80°C would have >85% of its nitrogen in ammonia gas. With ammonia inhibition, we would expect high odor generation and much slower rates of compost stabilization.

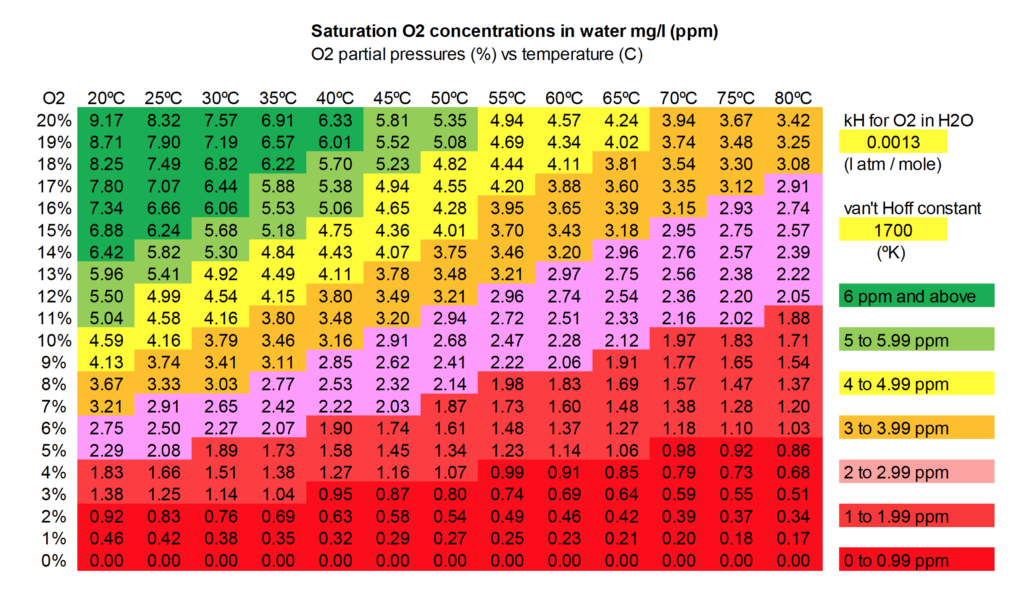

High temperatures have been shown to inhibit general (non-feedstock specific) composting in two ways. First, is the fact that bio-oxidative processes have been shown to roughly increase by a factor of 2x for every increase of 10°C up to around 65°C, and then drop off sharply at higher temperatures due to temperature inhibition.

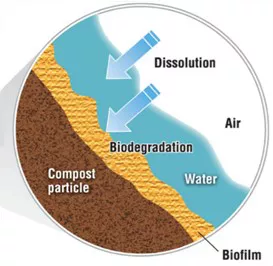

Second, is the inhibition caused by lower oxygen availability due to the inverse relationship between temperature and oxygen solubility in the liquid film layer. The explanation is as follows: each composting particle is covered in a thin water layer, or biofilm, as shown in Figure 1. The combination of oxygen concentration in the air space and the temperature in the biofilm determine the amount of oxygen that the biofilm can carry (this relationship is shown in Figure 3 published by the UK Environment Agency). The aerobic bacteria that do the composting reside in the biofilm. High dissolved oxygen levels (>3.5ppm) have been shown to provide rapid stabilization (conversion of bio-available solids to CO2) and low odor production.

We want to learn more about your project goals. Call or email us to get started.