The California Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery (CalRecycle) defines a “vector” as the following: “Vector includes any insect or other arthropod, rodent, or other animal capable of transmitting the causative agents of human disease or disrupting the normal enjoyment of life by adversely affecting the public health and well-being.” (Title 14 § 17225.73). Neither during our 30 years in the industry, nor in the literature review we have reviewed, have we been able document a pathogen being transmitted from a composting facility to a human via a vector. It appears that basic composting vector control methods have been highly successful. What we have seen is nuisance vectors in the form of insects, rodents, coyotes, and birds. The last category, birds, also can pose a risk to aviation.

The most common nuisance reports we receive from clients are of vectors damaging items made of soft materials. We have heard of coyotes in Oregon chewing on temperature probe cables, birds in California pecking through pressure sensor cables, and rats in Washington chewing through fabric covers. To give you an idea of frequency of these issues, we supply repair services and parts replacement at dozens of composting facilities each with from 10 to 150 sensors and we hear of vector caused damage about once every year or two. In the case of the coyotes, the answer was to clear the nearby scrub brush to deprive them of cover. In the case of the birds, installing chicken wire over the fixed pressure cable stopped that problem. As for the rats, our Washington client stopped using the fabric covers altogether so there nothing for the rats to chew on.

The most serious vector concern we encounter is the possibility of a composting facility increasing the likelihood of airplane bird strikes near airports. Many of us have experienced the gigantic flocks of seagulls and crows that swirl around the working face of a landfill. They are attracted to the non-stop smorgasbord of food waste that is constantly being spread out in relatively thin layers over a large area before they are covered mostly with dirt. Thankfully composting facilities aren’t operated this way. Composting facilities create compostable mixes that sequester most of food waste at the beginning of the process and then make relatively deep piles that minimize the exposed surface area. We have worked at a number of facilities located near airports that have demonstrated that composting can be done without attracting problematic concentrations of birds.

| Facility | Start-up Date | Vector Attracting Feedstocks | Tons/yr | Distance to Airport (ft) |

| LRI | 1998 | Food waste | 75,000 | 2,000 |

| Port Angeles | 2004 | Biosolids | 2,000 | 1,000 |

| Napa | 2019 | Food waste, grape pomace | 64,000 | 500 |

| American Organics | 2021 | Food waste | 100,000 | 3,500 |

Vectors are drawn to composting facilities primarily by sources of food, and to a much smaller extent, to sit on top of a warm pile in cool weather. The primary feedstock of concern is food waste (ref 1) that is either mixed into green waste or is a component of mixed solid waste. Biosolids and manures can also attract insects and a few birds, but these are readily managed using methods elaborated in EPA’s 40 CFR Part 503 standards. The keys to minimizing vector attraction at composting facility that accepts vector attracting feedstocks are:

Freshly tipped food waste left too long tends to attract vectors. BMP’s for handing food waste include:

In our experience, the only additional vector control method employed in the compost feedstock pre-processing areas has been to deploy rodent bait stations. These precautions have proven effective at minimizing vector attraction at the front end of numerous composting facilities. This has been true even at large facilities located in proximity to airports.

An extended bed or bunker walled biolayer Covered Aerated Static Pile (CASP) can limit vector access, rapidly biodegrade food waste, and capture leachate.

Vector access to food waste is through the surfaces of the composting pile. Most of the food waste in the mix will be inaccessibly buried deep in the pile, but some will be near the surface. The potential exposed surface area can be greatly reduced in extended bed or bunker style CASP’s where piles are adjacent to neighboring piles and/or walls. The potentially exposed area is thus limited to the top surface and front slope of the pile. It is standard practice to cover these surfaces with >12” of biolayer material consisting of compost that has been through the active phase or some other non-putrescible organic material. This biolayer cover insulates the pile so that the food bearing mix underneath is not only covered and hard to reach, but is also rapidly heated to temperatures in excess of 120°F. These elevated temperatures effectively discourage foraging.

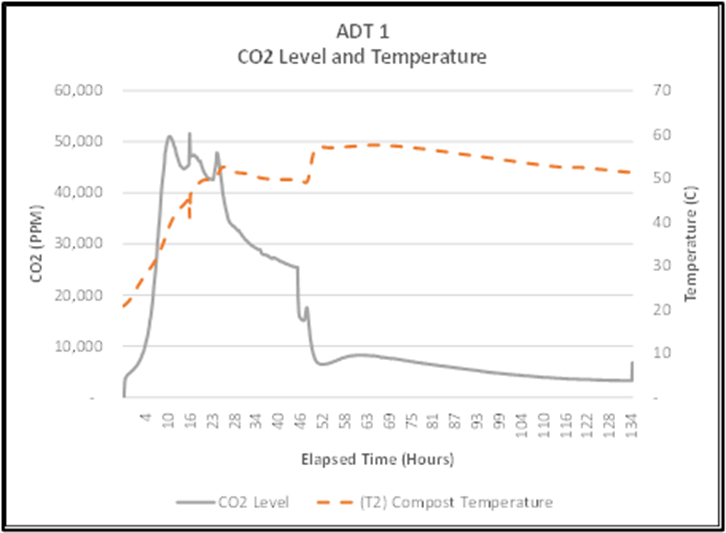

The rate at which composting degrades food waste to a non-vector-attractive state depends on the rate of bio-oxidation (aka composting). Achieving high rates of bio-oxidation early in the process starts with making a BMP mix, whose simple metrics include C/N, density, % moisture, and providing semi-optimized process conditions of temperature, oxygen, and pH in the pile. Ideally the CASP’s aeration and control system provides a wide range of feedback-controlled aeration rates to achieve and maintain these semi-optimized conditions. The speed of bio-oxidation is measurable by the production of either CO2 or heat, or the consumption of oxygen. High peak aeration rates are required to supply surplus oxygen and provide adequate cooling to keep the process from becoming inhibited by either low oxygen availability or by excessive temperatures. A typical curve of this intense early bio-oxidation is shown below. In these process conditions the food waste content in the mix is degraded in 2 – 3 days to the point where it is no longer attractive to vectors.

Uncontrolled leachate can be another vector attractor as it provides prime breeding grounds for bug larvae, mostly flies. The first step in controlling leachate is to minimize the volume created. Extended bed or bunker style CASPs do this by minimizing the total footprint of the active compositing pile. The aeration floors themselves should be designed to efficiently capture the water that either fall on an exposed floor or percolates down through the pile. In most circumstances, surprisingly little water percolates all the way through the pile to the floor. This is because the pile is constantly being dried out by the combination of bio-oxidative heating and forced aeration; the compost generally has unused water holding capacity that absorbs precipitation. And finally, the grades and collection points of the working surfaces adjacent to the CASP should be designed to eliminate run-on or run-off water. In this way storm water isn’t comingled with leachate keeping the total volume of high nutrient water to a minimum.

(Ref 1) https://www.biocycle.net/food-scraps-composting-and-vector-control/